By Edith H. Wheeler

From our July 1971 issue

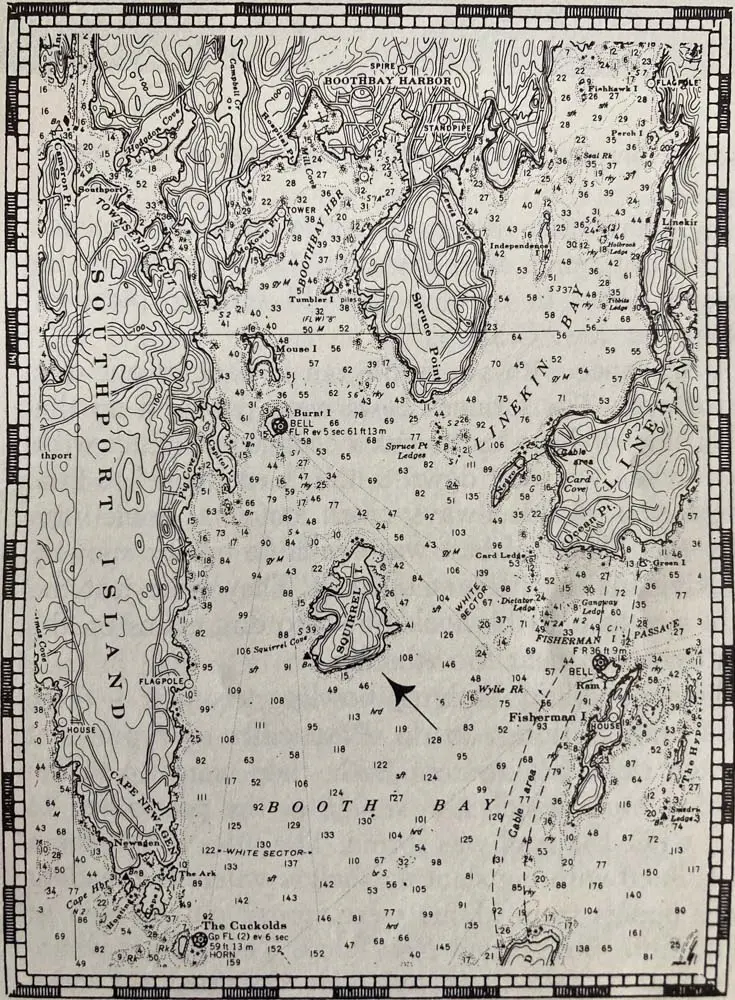

When I was a child, Squirrel Island was another name for heaven, with the blue sky overhead and the blue sea all around it. From 1878, when I was an infant of six months, until 1905, when I was married, I spent part of every summer there.

My grandfather, Jacob B. Ham, first mayor of Lewiston, was one of a group of men from that city — including U.S. Congressman Nelson Dingley and his brother Frank Dingley, founder of the Lewiston Journal — who bought the island in 1870. The deed was made out to Jacob B. Ham, who transferred it to the Squirrel Island Association when it was incorporated by the Maine Legislature in 1871.

The price of $2,200 paid for the island included two farmhouses and 60 sheep. Besides two small beaches of clean white sand, ideal for bathing, there was a spring, which for more than a hundred years had provided water for vessels. The new owners of the island sent a sample of the spring water to a professor of chemistry at Rochester University, New York, who reported it the purest water ever tested there — even more so than Poland Spring water, which held the record up to that time.

On June 22, 1871, 22 charter members of the Squirrel Island Association met on their newly acquired property to parcel out lots for summer residences. That season, 12 simple cottages were built, most of them along the central ridge, then bare as a bone, facing Southport, of which town we were a part. Building-lot certificate number 1 was issued to Grandpa Ham, who served as president of the association the first three years.

My first clear memory of Squirrel Island is fixed by the date 1884. That was the year James G. Blaine of Maine was the Republican candidate for president of the United States, and a large campaign picture of him hung on the cottage wall. It must have been soon afterward that Grandpa built a more commodious cottage, using the original one as an ell, for he died in 1888.

In 1884, the Ham cottage consisted of three small rooms downstairs. The upstairs was undivided except for curtains affording semi-private partitions. A trap door in the floor of the dining room covered a hole in the ground, which served as a refrigerator. Life was strictly a do-it-yourself affair. Someone had to go to the spring for drinking water, to the well in back of the house for washing water, to the farmhouse for milk, to the little store for groceries, to the post office for mail. Wood was the only fuel and kerosene lamps the only light. Every cottage had its woodshed with a private corner, which served until sewers were put in after 1900.

At night, we could see three lighthouses: Burnt Island in the harbor; Ram Island close by on the east; and 17 miles farther east the revolving light of Monhegan. Seguin Light was visible from the other end of the island. As we sat on the porch at sunset, a path of gold led across the water to Southport.

Squirrel Island was the pioneer summer colony in Maine, but by the 1880s the idea had spread, especially in the Boothbay Harbor region. The two-hour steamboat trip from Bath to Squirrel Island included stops at Westport, Riggsville, Five Islands, Isle of Springs (MacMahan development was still in the future), Southport, and finally tiny Mouse Island, scarcely larger than the thriving hotel which was built upon it. The earliest steamboats I remember are the Samoset and the Sasanoa. The latter was early displaced by the Wiwurna and the Nahanada. A little later, the Winter Harbor was added to the fleet of the Eastern Steamboat Company. Besides these regular trips twice a day each way between Bath and Boothbay, the graceful Islander from Gardiner called at Squirrel twice a week, and the big black-and-white Enterprise lumbered in from Portland every week, mainly with freight.

Once arrived at the Squirrel Island wharf, you made your way on foot over the boardwalks, which led to most of the cottages, about 60 in number in 1884. There were no vehicles — not even a bicycle — other than the one-horse cart, which transported baggage and occasional articles of freight over the rough natural terrain.

The Chase House in 1881 offered board and room at $8 to $10 a week. The farmhouse also took a few boarders. Fishermen came around early in the forenoon with gleaming mackerel caught that morning; tinkers were five cents each. In the season, a grizzled “blueberry man” appeared with a bushel basket of the luscious berries, which he measured out according to order.

My grandfather usually bought a bunch of bananas at the beginning of the season. One day, when he brought them in, my five-year-old brother pleaded, “Hang ’em low, Grandpa.”

A rail fence with a turnstile ran in back of our row of cottages. The farmer’s cows were pastured on the other side, and we had to risk a chance encounter with them when we went down to the “back shore” to fish. There, you could always catch cunners, sometimes rock cod. Plenty of bait was available on the spot by cracking snails with a small rock. They were just the right size to bait the hook. We also dug clams on the muddy beach near the wharf.

Rowing, sailing, bathing, bowling, croquet — there were endless things to do. Practically everyone met the 10 o’clock boat from Bath, then went up to the reading room, which also served as the post office, to wait while the mail was sorted. The sides of this room were lined with big slanting shelves where the leading daily papers from Maine were spread out, as well as some from Boston and New York. The shelves where the papers were displayed were designed for those who read the headlines standing up, but high stools were provided in front of the shelves for more intensive reading. A picture of Grandpa Ham as first president of the Squirrel Island Association hung on the wall. When the mail was sorted, Major N. B. Reynolds — who was association president from 1883 to 1889 — called off the names of the lucky ones, who answered, “Here,” and reached out their hands. Regular boxes and a window were installed some years later.

Opposite the reading room was a little red building, Fickett’s bakery, where the Spa was afterward located. Another little red house was the Squid printing office, where the Dingleys published a four-page seaside news bulletin. This tiny building nestled down at the foot of the craggy knoll occupied by the Frank Dingley cottage like a bird under its mother’s wing. Every Monday morning, a young reporter called at all the cottages to get the names of new arrivals for the week. The weekly issue also contained items of interest to the community.

A well-known personality of that era was Ab Lewis, who took out sailing parties in his big yacht, the Yolande. He also played the accordion for Saturday-evening dances.

The early Squirrelites were a joyous group, but they also were God-fearing people. On Sunday, all ordinary activities ceased. Religious services were held from the beginning, the first one in a grove with Professor Benjamin Hayes of Bates College as the preacher. Later, the services were held in the assembly room over the bowling alley. In 1879, the little chapel was built at a cost of $1,100 and dedicated in 1880. There were no pulpit or pews, only settees. Most people attended dressed in their best Sunday clothes, though the rest of the week they wore anything that came handy. From an early time, a distinguished organist came from New York as a summer resident — Professor Bowman, who produced unbelievable harmony from the little cabinet organ. His daughter Bessie had a beautiful contralto voice and often sang solos.

Sunday afternoons, there was a general exodus to the South Shore. People took cushions, reading and letter-writing materials, and formed little groups all over the rocky shore facing the open ocean. When the wind was right, the surf was spectacular. To get to the South Shore, we passed through a striking natural formation called Cleft Rock. The walls rose 10 to 15 feet high on each side, almost perfectly perpendicular, as if built by man. Once each summer, a Sunday-afternoon service was held on South Shore. It was unforgettable: singing Jesus Savior, Pilot Me Over Life’s Tempestuous Sea, as we looked out to the boundless horizon and heard the waves dashing on the rocks.

Two things I especially remember of that early period. One is going over to Boothbay Harbor to see a whale. The other is watching from Chase Beach after a big storm the big four-, five-, and six-masted sailing vessels — sometimes eight or 10 of them — which had taken refuge in Boothbay’s magnificent harbor. It was a grand sight to see them majestically making their way back to sea with all sails spread.

The decade of the ’90s was marked by great changes in the life of the island, many of them due to the coming of A. H. Davenport of Malden, Massachusetts. In 1887, he built houses at Spring Cove for himself and his wife’s sister, identical except that his had a round tower at the comer. The houses were known as “Tweedle-Dum” and “Tweedle-Dee.” Mr. Davenport’s steam yacht, the Carita, lay at anchor in the cove among the lesser boats, ready to take friends — especially young friends of his daughter Alice — out every afternoon. The boat was succeeded some years later by the larger Alicia.

Mr. Davenport built many fine cottages to sell or rent to desirable people and built the Spa in 1900, which he sold to Alton Grant for $6,500. He was largely responsible for the building of Squirrel Island Inn after the Chase House was destroyed by fire in 1893. He put in some of the island’s first sewer lines and maintained them at his own expense. Among numerous other good works, he also gave the community the beautiful library building, with $1,000 worth of books to start it off.

By then, the chief interest in sports had changed from croquet and bowling to tennis and baseball. Crowds sat on the board sidewalk and rocky slope above the common to watch tennis tournaments and baseball games. Here again, Mr. Davenport’s interest resulted in clay tennis courts to replace those of the natural grassy surface. The Casino was built in 1890, affording a place for entertainment and dancing.

I remember my pride in a bathing suit. It was of navy-blue flannel with knee-length bloomers, covered by a full skirt below the knees and trimmed with three rows of white braid. The braid also adorned the neck and short cap sleeves.

Senator William P. Frye of Lewiston was not one of the original settlers, but he built a large cottage in the ’80s, and his seven grandchildren, the Whites, were an active element in the life of the island in the ’90s. Friends of this family glibly recited the children’s names in their order of age: Willie, Wally, Emmie, Tommy, Don, and the baby. Five of the six boys, including the baby (Harold), became well-known businessmen in Lewiston and Auburn. Don was a star on the Squirrel Island baseball team. He later married my cousin, Ethel Ham. Wally — as Wallace H. White Jr. — succeeded his grandfather as U.S. Senator from Maine. We younger people were greatly interested in the romance of a handsome couple — Florence Brooks and Robert Whitehouse — many of whose descendants now live in Portland.

Life in the ’90s and through the turn of the century was a little more sophisticated. This was reflected in the independent government of the Squirrel Island community through the formation of the Squirrel Island Village Corporation, which obtained a charter from the state in 1903. The original association had made no provision for community revenue other than that received from the sale of shares. As a succeeding generation drew away from the starkly simple life and demanded more comforts, a new source of revenue by assessment was required.

Under the Village Corporation charter, it was granted a lease by the association of the entire island property for 999 years and given power to assess a legal tax upon the property of each person. The original association retained the title to the land, and its directors made all leases of lots, which, if transferred, also had to have the approval of the parent association. Otherwise, the Village Corporation assumed responsibility for direct government of the community, a system which, from the beginning, had included the choosing of a superintendent as year-round resident, the licensing of a storekeeper, etc.

Under the new charter, it was arranged for a percentage of the taxes paid to Southport — exclusive of state and county tax — to be returned to the Squirrel Island Village Corporation, which, in turn, assumed all of its own municipal obligations. Among the unique provisions of the new charter, drafted by Seth M. Carter of Lewiston, was one granting equal votes to women for the first time in the state of Maine and probably in New England. Non-residents also were allowed to vote.

On the 50th anniversary of the Squirrel Island Association, it was honored by a special 24-page semi-centennial edition of the Lewiston Journal Magazine Section, published on August 20, 1921, as “The Plymouth of the summer colonies.” The success of the Squirrel Island colony was said to have changed the barren coast of Maine from Kittery to Eastport into a vacationland, which “peopled the entire shoreline with summer guests.”

Today, the Squirrel Island Village still flourishes at a sedate and quiet pace that probably the original founders would not find radically changed if they were a part of our present world, save for such refinements as electricity and plumbing. Squirrel Inn was destroyed by fire in 1962 and has not been rebuilt. There are about 110 summer cottages — clapboarded, gabled, and, in some instances, turreted — which average perhaps 12 rooms in size and often nestle so closely into the peaceful woods as to be invisible from the concrete walks, which replace the earlier boardwalks. There still are no roads and no automobiles on Squirrel Island; hence there are no gas stations, shopping centers, pizza parlors, neon signs, or billboards.

About 500 summer residents comprise the present secluded Squirrel Island colony, many of whom are fourth-generation inheritors both of their island homes and the Squirrel Island philosophy: “the simple, orderly outdoor life close to the sea and the woods.”