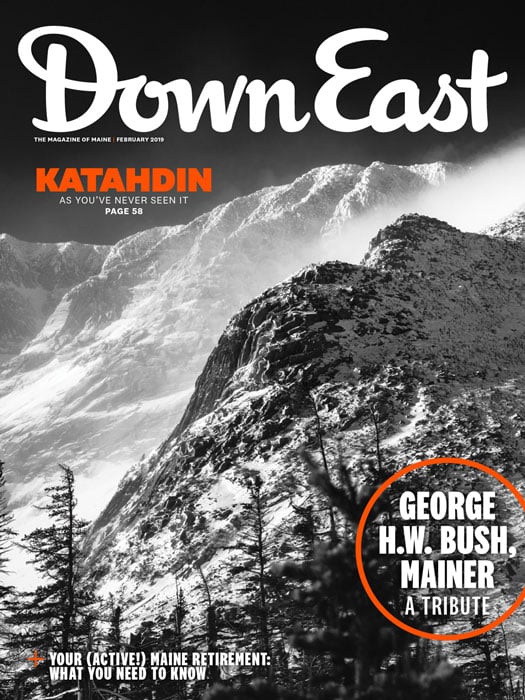

How growing up where George Bush summered shaped one writer’s views on privilege, politics, and hometown pride.

By Joshua Bodwell

[cs_drop_cap letter=”I” color=”#000000″ size=”5em” ]n the early 1980s, I was a latchkey kid from a divorced family in Kennebunk-port. After school, in grubby Wranglers with torn knees, I rode my red Schwinn a few blocks to the village square to meet friends. We were wild. We scavenged returnables and bought candy with the money; when there was no money, we shoplifted. We lobbed rocks into the water from the bridge, and we hid in bushes and pinged cars with acorns. We ranged through town like a pack of dogs until the streetlights clicked on and we pedaled furiously for home.

It was a childhood not unlike many Maine childhoods, except that hanging like a fog over my coastal village was the presence of George H.W. Bush and his family. In my adulthood, my awareness of this fact has grown into a twisted knot of both pride and resentment: I love my hometown, but I don’t love that the name “Kennebunkport” is now synonymous with the Bushes’ summer home.

I remember one Memorial Day in the mid-1980s, when Vice President Bush gave a speech in Dock Square. Back then, the village’s old buildings were crooked, their cedar shingles curled, their clapboards in need of a scraping and painting. Clustered around the square was Smith’s Market, a pharmacy, a barbershop, a hardware store, and Nick the Cobbler’s, a tiny, sweet-smelling shop where my older brother used his paper-route money to buy a sheath for his knife. The village seemed to have lazed along unchanged since my father’s 1960s youth.

Rather than listen to the Memorial Day speech, my friends and I watched Secret Service agents line the rooftops of buildings that ringed the square. We wondered about their guns. We groaned with jealousy, having dreamt for years of running along those roofs ourselves. But quietly, I felt a small thrill knowing that no other town in the country was right then hosting the vice president of the United States of America.

Over time, that luster dissolved. The speeches in the square tapered off. The once-dramatic motorcades that raced Bush to Walker’s Point came to feel like a nuisance. The road checkpoints set up during his visits were not glamorous but annoying. Occasionally, an international leader such as Thatcher or Gorbachev would visit and send the town into a spiral of excitement — or a chasm of chaos, depending on whom you asked. Where the Bush clan was concerned, most locals settled into one of two camps: ardent supporters or dismissive hecklers. Either stance seems too easy to me now.

Today, Kennebunkport has earned a reputation as a ritzy seaside village — certainly by modest Maine standards. During my late teens, the big money arrived, seemingly overnight, to straighten the crooked buildings and scrape away the flaking paint. “Investors” have flocked ever since, eager to remake the town as a theme-park version of itself — or, worse, as an unholy mash-up of New England-meets-Miami. The town’s tony makeover became a constant reminder to me that you don’t need to be destitute to feel poor. It would be disingenuous to blame Bush for my hometown’s transformation. Yet it’s also impossible not to consider the impact of decades in the national spotlight. Money follows power, as surely as the high-tide waters beneath Dock Square seek a path of least resistance among the pilings.

In at least one way, however, Bush’s summer residency in my hometown was a gift: his presidential term coincided with my rebellious high school years, giving my friends and me a target for our revolt. In 1991, New York–based activists from the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) came to town to protest, furious the Bush administration wasn’t doing more in the face of a pandemic and knowing they could attract national media attention. They wore black T-shirts emblazoned with bright-pink triangles. They shouted into megaphones and held “Silence = Death” signs. They flopped to the ground all at once and pretended to be dead. They handed out condoms. Later, while most of the activists marched on Walker’s Point, shouting and banging drums, a few hung back to barricade themselves in the bell tower of a church off Dock Square. They hung a white bedsheet spray-painted “Ask not for whom the bell tolls!” and clanged and clanged the church bell until, finally, police knocked down the door.

ACT UP’s visit brought an issue of international importance to our doorstep, and we had Bush to thank for it. At the protests, I watched people getting arrested not for theft or assault but for activism. It unnerved me: people whose friends and family were dying, pleading to be heard and being met with indifference. Bush seemed to me then like an out-of-touch, rich, Reagan-era conservative who had mired us in the Gulf War, and it was invigorating to focus our fear and anger on him.

Time and context have blurred my feelings. History may look back on George H.W. Bush as an imperfect leader and man but also as the last fairly moderate Republican president.

When I mention where I grew up, people sometimes respond with, “Ah, yes, Kenne-Bush-port,” which makes me cringe. Sometimes they offer a pregnant, lilting, “Ohhhh,” as if to suggest they know all they need to know about me based on their impression of today’s Kennebunkport, the ritzy seaside village. “I grew up a poor kid in a rich town,” I’ll reply. I say this even today — that kid in the grubby Wranglers, with all his lacking and wanting, won’t allow me to let go. But today, I say it without bitterness.

The truth is, my childhood provided me a front-row vantage on the privileges of wealth and power. I learned at a young age that there is a ruling class and a class that serves it. I’m grateful for that. The class-consciousness I developed in Kennebunkport became the anchor of my political conscience. And my hometown is my compass, my reminder that when our leaders — no matter how affable they seem — drift off course, we need to climb into the bell tower, bolt the door behind us, and clang and clang that bell.