By Jaed Coffin

From our April 2025 Home & Garden issue

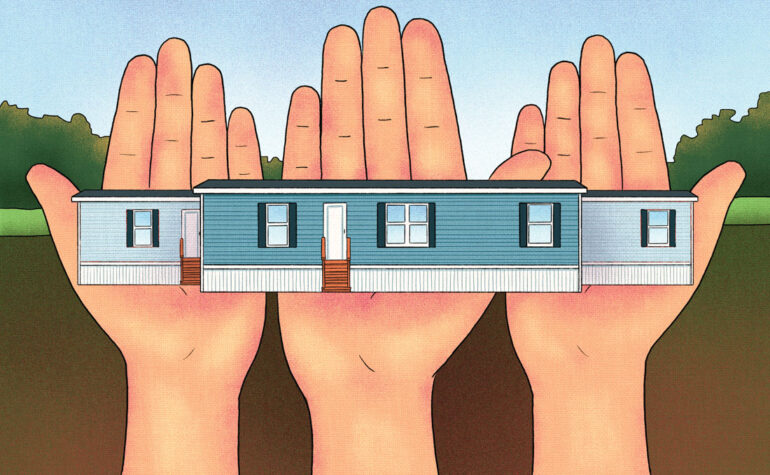

Since 1954, the family that owned Linnhaven Mobile Home Park, in Brunswick, had a reputation for running a tight ship. The park developed in a desirable spot, a short drive to Brunswick’s downtown in one direction and to a lovely tidal bay in the other, on a property backdropped by blueberry fields. Then, last spring, the soon-to-retire son of the Scarponi family decided he was ready to cut ties with the property and began entertaining offers from potential buyers. As is typical in mobile-home parks, Linnhaven’s residents owned their homes but rented the underlying land. So when word spread that Linnhaven was for sale, residents feared the future would unfold as it has elsewhere across the state and country in recent years: an out-of-state buyer would snap up the property, jack up their rents, and price them out (roughly a fifth of Maine’s 686 mobile home parks belong to out-of-state investors).

Last fall, though, after months of organization and negotiation, residents pulled off a rare feat, collectively purchasing the park to the tune of $26.3 million. Now, the 47-acre park is called Blueberry Fields Cooperative, and while it’s not the first resident-owned mobile-home community in Maine, it’s the first that successfully leveraged new state legislation requiring park owners to engage in good-faith negotiations with residents before selling to anyone else. To pull it off, residents got advisory support from a mix of nonprofits and state and local government. Now, with 278 homes, Blueberry Fields is the largest of Maine’s 12 resident-owned parks, all of which are in midcoast and southern Maine except for two in the Bangor area.

Amid a statewide and national housing crisis, the lessons from Blueberry Fields resonated beyond state lines. “Residents of a Mobile Home Park Join Forces to Buy Their Community” a New York Times headline announced. For many, Blueberry Fields became a case study in common-sense housing policy, with Maine’s new law helping to level the playing field for average citizens.

Recently, sitting in her living room, on Scarponi Drive, Janet Fournier looked back on the last several months with a mix of awe and exhaustion. Now the president of the Blueberry Fields co-op board, she compared the process of buying the park to bringing a child into the world. “The first trimester, it was all fear and anticipation,” she said. “Then, it was all about momentum, making sure everybody was on board.” The third trimester involved “getting ready for the baby to be born.” The birth, as it were, was triggered by residents’ formal vote to approve the purchase, held in the Brunswick High School cafeteria, which sits behind the park, across the blueberry field. Ever since closing papers were signed, Fournier said, she and her neighbors have been learning how to “raise the infant.”

Seated next to Fournier was Tom Benoit, vice president of the board. He devotes much of his energy toward figuring out the right rules for the community to follow. For now, many of the rules in place under the previous ownership remain. But at monthly meetings, residents are wrestling with what to do now that the property is governed more democratically. “It’s a social experiment,” Benoit said, sounding a little weary. In a recent meeting, there was debate about the speed limit on the community’s roads, currently set at five miles per hour. “Some people think we need to put in speed bumps,” he said, “while some people think we should raise it to 15!” Another topic of debate: the Scarponis required lawn furniture to be brought inside by early fall, and holiday decorations weren’t allowed out past New Year’s Day. Perhaps there’s room to ease up.

Benoit sometimes drives around the park wrestling with the enforcement of existing rules, like keeping trash bags in bins or bringing bicycles in from driveways. “It can be funny how to balance all those things,” he said, adding that he tries to remind people, “The rules we’re putting in, they might not be great for you as an individual, but they’re going to help the community as a whole. This is a $26 million property. We have to keep it nice.”

Fournier’s goal is to balance the immediate needs of the community against larger issues. In the middle of the park, for instance, stands a building that used to serve as the Scarponi family home. Some residents would like to see it repurposed as a common space, but Fournier worries about the added financial obligation of upkeep. And while each of Blueberry Fields’s homes has access to town water, almost all of the units sit on top of individual septic tanks that are likely nearing the end of their useful lives. The cooperative anticipated having access to state and federal funding for infrastructure improvement, but amid the new presidential administration’s efforts to slash the federal budget, Fournier isn’t as confident about tapping into those funds.

For now, the residents of Blueberry Fields are continuing to raise their infant, growing pains and all. Benoit often speaks with residents from other parks, in Maine and beyond, and he urges them to take on resident ownership even though it can at first seem like an insurmountable challenge and invariably will involve some headaches. “I really encourage them to think about their future, because this is one of the last bastions of affordable housing,” Benoit said. “If communities don’t get together and buy these places, there won’t be any left.”