By Kathryn Miles

Photographed by Michael D. Wilson

From our December 2016 issue

At the Appalachian Trail Café in Millinocket, Gary Allen sticks out without being conspicuous. To his right, a long table of locals knock back bottomless cups of coffee. Behind him, a couple of thru-hikers are busy adding their names to the hundreds that tag the café’s walls and ceiling. The former group wears muted flannel and Yankee reserve; the latter, a mishmash of synthetic fibers and trail funk.

With his scarlet running shirt, lean frame, and megawatt smile, Allen glows like a supernova as he holds court over an enormous plate of eggs and bacon and smashed tater tots. The 57-year-old is just back from his third year running the 31-mile ultramarathon at Burning Man, the storied Haight-Ashbury-meets-Mad-Max carnival of art, anti-commerce, and radical gifting in the Nevada desert.

For his contribution this year, Allen brought 10 pounds of lobster meat he shucked, froze, and packed into his checked luggage. It leaked during the flight, saturating everything in his duffle bag. And so now, as he inhales big bites of egg and potato, he’s demonstrating how he hung all of his clothes and camping gear to dry on the security fence of the Reno Airport while evading TSA and waiting for his rental car.

It’s a good story. And Allen tells it with such zeal that it draws the attention of both the locals and the hikers. Here’s this guy who handed out lobster salad on romaine lettuce, then ran for hours in blistering desert heat, wearing nothing but short shorts and leg warmers that look like they were stolen from a Muppet — all the while smelling like some poor sternman’s bait bag. It was, concludes Allen with enthusiastic crescendo, pretty much the time of his life. Except for maybe that time he ran the New York City Marathon, even though it had been cancelled on account of Superstorm Sandy. Or the time he schlepped 50 miles a day from Maine’s Cadillac Mountain to Washington, DC, for President Obama’s second inauguration. Or the countless lonely races he’s run on his native Great Cranberry Island, a 2-mile–long nub of granite off Mount Desert Island — and one that he’s traversed so many times he can lap it with his eyes closed, navigating only by his sense of smell.

Long-distance runners have a reputation for being as wacky as they are driven. Allen is proof positive of both. As coach of the Mount Desert Island Middle School cross-country team, he trains his squad mostly by playing zombie invasion games behind the school. He has a screaming-loud stocking hat for every occasion — especially the formal ones. He’s proud of his skull ring (made by his wife, Lisa Hall, a jeweler on MDI) and his crow tattoo (the insignia of the running club he co-founded in 1991). He’s ebullient and sometimes long-winded but knows how to affect reticence with an authenticity that would make any fellow Mainer proud. He treats everyone like his new best friend and begins each conversation with, “Hi. I’m Gary Allen,” assuming that’ll mean something to the person listening.

It does to our waitress.

“The marathon guy,” she responds with a smile.

The marathon guy. Allen’s run a hundred of them and won his age group in more than a few. He’s made a regional name for himself after deciding to run the Boston Marathon not just on Patriot’s Day, but also to kick off each new year. He’s the founder of the Mount Desert Island Marathon and the Great Run, a six-hour ultramarathon where competitors simply run back and forth on Great Cranberry Island as many times as they can (fellow Mainer Leah Frost won it this year, logging 46.2 miles, or 23 laps, in 5 hours and 50 minutes).

Millinocket needed a boost, sure. But not a handout. And definitely not more maudlin press.

But none of that means much to our waitress or the other 4,500 people who call Millinocket home. When they talk about a marathon, they’re talking about the one Allen first organized last year — the one that put the town on the long-distance map after Runner’s World picked up the story. The one that has more than 1,000 people clamoring to fly across the country for the opportunity to run here in December.

Like most of Allen’s schemes, this one started on a whim. Around Thanksgiving last year, he read yet another newspaper article characterizing Millinocket’s economic woes.

“I couldn’t unread it,” he explains. “It’s not like I set out to find a little town to help. It’s more like a little town found me.”

There’ve been a lot of those articles since the Great Northern paper mill closed here in 2008. In the years since, Millinocket has become a symbol for the failure of America’s manufacturing monotowns.

That doesn’t sit well with locals here. And it rubbed Allen the wrong way last fall too. Millinocket needed a boost, sure. But not a handout. And definitely not more maudlin press. So Gary Allen decided to do what Gary Allen does best: he organized an impromptu marathon.

In the spirit of Burning Man, this race was open to all and charged no entry fee. Instead, Allen suggested that participants take the money they would have spent on registration and spend it in Millinocket. He didn’t advertise any of this except to post it to his Facebook page. Nonetheless, about 50 of his friends agreed to show up for what may well have been America’s first flash-mob marathon.

Allen mapped the course on Google Earth. It’s a gorgeous one: a lazy loop with lots of views of Katahdin and several miles on the iconic Golden Road, a 96-mile stretch of gravel connecting Millinocket and the Canadian border, before it drops back down into town for a finish at Veterans Memorial Park. Allen warned participants that they’d need to be totally self-sufficient during the race. He printed out slips of paper detailing how to stay on the course. After they were done running, he figured they could have lunch or do some holiday shopping, then fuel up their cars and head home. Millinocket might not even realize they’d been there.

But word got out around in close-knit Millinocket. By the time Allen rolled into town, local businesses had emblazoned signs welcoming the runners. A high school junior showed up at the starting line and sang the national anthem. Locals set up a water station around the 5-mile mark and stood for hours guiding runners on the course and directing traffic. A cheering section assembled at the finish.

In other words, the marathon flash mob got flash-mobbed by the town they were supposed to be helping.

And in that moment was born an unlikely love affair between one of Maine’s most charismatic runners and a town looking to get back on its feet.

After last year’s race, townspeople asked Allen if he’d organize another one. He agreed. And he said he thought he could make it bigger, better.

Earlier this year, he returned to Millinocket with a surveyor who could certify the course as an official Boston Marathon qualifier — the only one in the country without an entry fee. As it turned out, Allen’s hastily drawn loop on Google Earth was less than 50 yards off the exact required distance.

“I felt like that was proof Millinocket is supposed to have this,” he tells me, as we stroll Penobscot Avenue, the town’s main drag.

But even more important than that, he says, is just how selflessly residents have embraced the race. While Allen and the surveyor were in town, a total stranger offered the two men a house to stay in for as long as they needed. That, says Allen, is the spirit of Millinocket — and Mainers in general, for that matter.

As we talk, Allen peeks in the window of each storefront and spends extra time looking inside the empty ones. There’s an admittedly apocalyptic feel to them: calendars still turned to 2008; discarded receipts and flyers bearing the same date. It’s the year the mill closed its doors. And like it or not, it’s impossible to talk about Millinocket without also talking about that fateful year and the effect of the closure.

For decades, the town was known as the “Magic City,” a nod to how it seemed to have sprung up overnight in what had previously been untrammeled wilderness. And there’s a sort of truth to that. Coastal Maine towns like Kittery and Berwick trace their histories back to the mid-17th-century. Even Augusta, the state’s landlocked capital, celebrated its bicentennial decades ago. By these standards, Millinocket, founded in 1901, is but a blip. And like the Greek goddess Athena, it seemed to emerge fully formed from the mill itself — first as dozens of tar-paper shacks and rooming houses; soon after, as an Anytown, USA, with a bustling main drag and orderly blocks of houses.

The town was built on the principle that everything — and everyone — should be within walking distance of the mill. At the dawn of the 20th century, that included the Syrian grocery, Lebanese bakery, and Chinese laundry. Flush millworkers shopped at jewelers and candy stores; they attended lavish papermakers balls and circus parades and watched heavyweight champions spar at the company pavilion.

Great Northern helped build the schools; it sponsored sports teams and offered complimentary landscaping whether you worked for the company or not. On graduation day, mill recruiters would show up at the high school offering steady work to anyone who wanted it. Most of the boys in any senior class accepted.

When the mill shut its doors a century later, it took much of the town’s vibrancy with it. Millinocket, it seemed, had lost its identity. In its place came a sadder one — the downtrodden, boarded-up, beat-up specter of what failed American manufacturing had wrought. No matter what they tried, residents felt like they couldn’t get out from under this characterization.

Jesse Dumais is one of them. When the 41-year-old Millinocket native ran for town council last year, regional papers picked up his story — not because of his platform, but because Dumais, who currently manages the town’s McDonald’s, is also a felon, convicted in 1997 of assault and conspiracy to commit murder. Dumais served his time and eventually became one of the town’s favorite sons. Here was a guy who’d found a second chance. Maybe he could help find one for his ailing hometown as well.

Dumais won that election. And, as a councilman, he says he is well aware of Millinocket’s challenges. The town’s population has been dropping steadily over the past 40 years. Today, its unemployment rate is anywhere between 15 and 25 percent, depending upon which source you consult. Even on the lower end, it’s a number well over twice the state and national rates.

Dumais says that’s because, for far too long, Millinocket put all its eggs in the timber basket. For the town to really get back on its feet, it’s going to take lots of little initiatives — what he calls a “bunch of small victories.”

The marathon, he contends, is a really big version of those victories.

“We don’t want pity,” he says. “And we don’t want to just survive. We are proud people. We want to find a way to thrive. The race is one of those opportunities.”

Above all else, says Dumais, the marathon and initiatives like it are a chance for Millinocket to finally carve out its own identity — not as a town in thrall to a mill, but as a town with its own plan and vision for the future, one that embraces everything wild and wonderful about the region.

That’s what brought John Hafford and Jessica Masse here. The couple grew up in Aroostook County, then headed to Boston for college and careers. Jessica worked as a researcher in molecular genetics at Harvard Medical School. John helped establish, then sell, a lucrative software start-up firm. When they decided to start a family, they looked around New England for the perfect place to do so. They decided on Millinocket.

“We wanted our children to be connected to the land,” Hafford says. “If you love the outdoors, this place has everything. And there’s so much potential in the town itself.”

Together, the two bought Millinocket’s Odd Fellows Hall. Half the first floor holds the offices for their marketing and graphic design firm, DesignLab; the other half boasts a stylish meeting room open to any community organization.

“The whole region is in this together,” says Masse. “If we can unify and work on common interests, we can actually shine pretty bright. A lot of us feel Millinocket has already reached a tipping point. It’s on the way up again.”

She and Hafford point to recent improvements like the arrival of broadband, the beautification of parks and properties, the launch of new trail systems that will bring more bikers and hikers to the area. And, of course, the marathon.

Thanks to that Runner’s World article last year, the race went viral. Requests to run it poured in from all over the country. Allen capped the number of participants for this year’s event at 1,000; still, every day, additional people post on the race’s Facebook page, hoping they can squeak in. Those lucky enough to land a bib number will be arriving in Millinocket this month from every state in the union. A professional race production company based in Boston offered to drive up and provide microchip timing for all the runners — at no cost to anyone. A port-a-john company offered their services as well. Local organizations have adopted each mile, promising to put out markers and some festive surprises too.

Once the competitors arrive, they’ll stay at local motels and camps and inns, and they’ll spend their money at restaurants and shops and convenience stores right when Millinocket needs it most. December, says Hafford, is a particularly lean month in the Katahdin Region: No more Appalachian Trail hikers or tourists looking to spot a moose or summit the mountain. Still too early for the out-of-state snowmobile traffic.

“So we’re left with all these vendors on the hook, just waiting. It’s so stressful,” says Hafford. “A thousand people coming into town is a huge shot in the arm for all of us.”

And that, agree Dumais, Hafford, and Masse, is because of Gary Allen.

If you’re skeptical about whether a once-a-year, free marathon can meaningfully change a town, you might be forgiven. I was suspicious too. After all, if Allen really wanted to foster change here, why not just charge an entry fee and donate that money to a local cause? Everything from animal shelters to breast cancer research has been funded that way for decades.

Allen admits he toyed with this idea of a donated entry fee, but it somehow felt dirty.

“I’m an out-of-towner,” he says. “It’s not my place to wander in and offer to charge for a race or decide where that money should go.”

Besides, he says, that’s the old paradigm. And it ignores what Allen believes to be a key human trait: the desire to do good for others.

Last year, the race’s winner, Sarah Mulcahy, spent her afternoon at a Millinocket pub with a group of other finishers. Afterward, some of them paid the checks of local diners, and others tipped the waitstaff 100 percent or more. One server said the gesture would allow her to buy Christmas gifts for her kids.

“That’s the stuff you remember,” says Mulcahy. “It’s not about a medal. Or even about a race. It’s an experience. It’s doing something for someone else.”

Allen agrees. “This is about radical generosity. And it’s all the more remarkable given that it’s coming from a sport known for its selfishness.”

Too often, Allen says, the solitary nature of running leads to what he calls “a self-absorbed me, me, me.” Runners take time away from their families to pound out miles; they traffic in personal bests and individual rankings. Allen says he spent a lot of his life guilty of that. It’s part of what made his run to the 2013 presidential inauguration so life-changing for him.

“I kept thinking, if I can inspire one person, raise one dollar, and survive the ordeal, then that’d be pretty cool.”

As it turned out, Allen inspired lots of people. As news of his attempt spread, local fire departments and cross-country teams met him at their town lines and paced him. Police provided escorts. Frat houses offered basement floors to crash on. Maine’s senators and representatives invited him to the inaugural ball. He politely declined, pointing out he had only the running clothes on his back. Instead, he agreed to meet with them once he arrived in DC. And by the time he got there, he’d raised some $20,000 for disabled veterans.

Millinocket Marathon participants have donated over $7,000 to the town’s public library and Our Katahdin, a nonprofit group promoting regional community and economic development. That alone, says Our Katahdin board member Nancy DeWitt, has done a lot to help the region.

But the heart of this new marathon paradigm, Allen says, is even better. Most runners aren’t choosing to support the race with donations, but rather, by shopping in stores and eating in restaurants. Along the way, they’re getting to know a town. They’re forging relationships that transcend race day. Already, some of last year’s participants have been back for a visit. Call it philanthropic adventure tourism. Or just call it a unique excuse to explore a previously undiscovered destination. Whatever you call it, every last resident I talked to agreed that it’s pretty spectacular.

On The Run

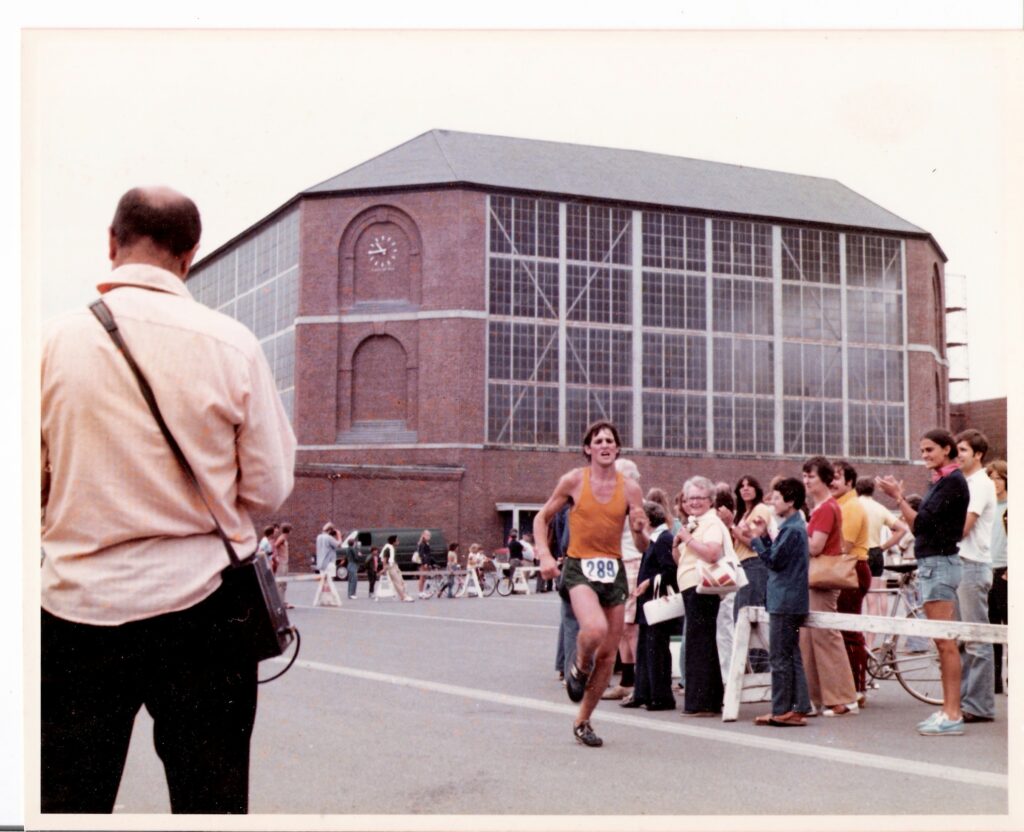

Allen is one of three dozen runners worldwide to run a sub-three-hour marathon in five different decades (fun fact: the only woman in that club is another Mainer, Cape Elizabeth native Joan Benoit-Samuelson).

Take Stephen Sanders, a former mill worker and current co-owner of Maine Heritage Timber. When Allen and I meet him, he and some of his crew are nailing a new display stand into the storefront they’d just bought. By the time the marathon rolls around this month, they hope it’ll be a high-end showroom for their work.

When Sanders sees Allen, he sets down his nail gun and comes out to shake hands, then offers the parking lot at his headquarters for any racer who wants to leave a vehicle near the course. He could also run shuttles, he says, if that’d be helpful. Anything to help support the race.

I try playing the skeptic. Just how transformational, I ask, could Allen’s model really be? Sanders looks at me like I’m crazy.

“Donations are fine,” he says, “But they’re a dead end. Gary is getting hundreds and hundreds of people to come to town. That’s a much bigger deal. We want people to know we’re moving up — that there’s potential here.”

Jessica Masse agrees. She uses words like “keen” and “brilliant” to describe Allen’s plan.

“He has the heart of a millennial,” she tells me. “Often it takes enterprising college kids to think out of the box like this. Getting visitors into our streets has an economic effect, but it also has a psychological effect on the town. He’s helped us all believe in ourselves again.”

She and Hafford have been on both sides of road races. They’ve seen what a bear it can be to lure participants with the same old entry fee and finisher swag. T-shirts and medals don’t cut it anymore – especially not when you’re trying to recruit people to fly across the country and then figure out how to get themselves to a town more than an hour away from the nearest airport. As it turns out, says Masse, the opportunity to participate in a local economy — especially one that really welcomes your business — is a surprisingly powerful draw.

Allen says he’s not surprised. He points to the MDI Marathon, one of his greatest accomplishments. “I’ve been organizing that race for 15 years, and it takes place at one of the country’s most well-known tourist destinations. I still haven’t had 1,000 people sign up.”

Gary Allen has spent most of his adult life worrying about things other than careers. He knows how to swing a hammer; he’s worked on fishing boats and even tried his hand as an organic farmer. But until recently, if you’d have asked him what he does, he’d have told you he’s a runner. That’s still true, but these days he characterizes his real work differently.

“Basically,” he says. “I throw pebbles into still pools.” He’s given formal talks on this theme at Burning Man and in front of running clubs around the country. And these days, it’s a metaphor you hear a lot in Millinocket. The town was pretty still when Allen showed up, and the race is creating some big ripples.

Tricia Cyr counts herself as one such ripple. She’s the co-owner of Moose Drop In, a consignment crafts store featuring only local artists. She and business partner Jennifer Murray opened the store just over a year ago. They say sales have been slow but steady during peak tourism season and steadily slow otherwise. So you can imagine their confusion when the store suddenly became packed on an otherwise quiet afternoon last December.

“All of a sudden there’s all these fit people in running clothes looking to buy stuff,” Cyr says. “It was crazy.”

Once they figured out what was going on, she and Murray decided to take selfies with each of the runners. They’re now displayed on her marathon wall of fame, which Cyr shows me after giving me a full-body hug by way of introduction and then berating Allen for not taking her with to Burning Man.

Cyr is loud and hilarious and utterly enamored of Allen. After the success of last year’s race, a t-shirt company in Portland announced a desire to sell shirts this year. Cyr thought it was a lousy idea and told Allen so. Then she and Murray wrote a grant proposal and purchased their own silk-screening equipment. A local artist sketched the design.

When we met, they’d already sold about 500 race shirts, which they’ve shipped as far away as Arizona and Washington State. They’re also now making shirts for local school sports teams, a job that used to get outsourced to a bigger city. Business, Cyr says, is good. Just recently, a local woodworker completed commemorative medallions for the race. Those are on display at Moose Drop In too.

Meanwhile, the event itself has become something bigger than even she or Allen could have imagined. Everyone Allen and I meet in Millinocket seems to have something to offer: Maybe a warming tent for runners? How about soup and hot chocolate? Or live music? There’s an artisan fair planned for the day before the race. Northern Timber Cruisers, the area’s snowmobile club, is hosting both a pre-race spaghetti dinner and a pancake breakfast. The Stearns High School booster club is running a family funfair during the marathon: in the spirit of the race itself, admission is free but donations are welcome. Local motels have been booked out for a while now, so residents are offering up rooms for runners.

Mid-December in northern Maine is a meteorological crapshoot. At the start of last year’s race, temperatures were in the low 50s. Racers competed in shorts and t-shirts. Allen has no idea what this year will bring. Could be a blizzard. If so, runners might not even be able to complete all 26.2 miles. But that doesn’t matter to him — or to most of the registered racers.

“Big things happen when you live your passions,” says Allen. Whether or not anyone crosses the finish line, he’s confident this will be a big day for everyone — maybe big enough to create more pebbles and more ripples.