Jensen Bissell manages Maine’s Baxter State Park, 210,000 acres of the most dramatic peaks, prettiest ponds, and finest trails east of the Rockies. Lately, he spends a lot of his time trying to keep people out of it.

(Or does he?)

By Brian Kevin

Illustration by Philippe De Kemmeter

[cs_drop_cap letter=”W” size=”5em” ]hen Jensen Bissell, director of northern Maine’s Baxter State Park, first arrived in Millinocket in 1987, the Great Northern Paper mills were booming, and local attitudes towards the park tended to range from indifference to disdain. The town was flush; few of the park’s modestly paid staffers could afford to live in it. It’s only recently, Bissell says, with the collapse of the forest products industry, that Baxter’s local cachet has surged. He remembers vividly the day in 2009 when the Heritage Motor Inn across from his office rebranded as the Baxter Park Inn — a moniker no business would’ve adopted during Great Northern’s heyday. He walked right outside to get a photo of the new sign, with its prominent visage of a snow-capped Katahdin, the park’s mile-high crown jewel.

“We have a bigger profile now, because in the last 30 years, everything else has fallen away,” Bissell told me recently. “But the park, all this time, has been the same park it’s always been. We’ll turn out the lights when society ends, that’s the way I look at it.”

In August, Bissell took the podium in front of a 100-person crowd in a Colby College lecture hall to deliver a presentation entitled “What Does ‘Forever Wild’ Really Mean? The Challenges of ‘Keeping the Park From Changing.’” It’s what Bissell spends a lot of his working hours thinking about — keeping the park from changing — and his efforts to that end have earned him both staunch admirers and vocal detractors. Arriving at Colby to address the biennial conference of the national Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC), Bissell wondered whether his audience might include a bloc of the latter.

Off the clock, the 63-year-old Bissell exhibits classic Yankee reserve. He describes himself as an introvert who powers through it for the sake of his job, and in a professional capacity, he is indeed a terrific communicator: warm and natural, straightforward and concise, lots of eye contact, drops your name every so often. At Colby, he led off with a self-deprecating inside joke.

“I agreed to do this, I think, almost two years ago,” he said, pausing for effect. “It seemed like a good idea at the time.”

The line got a laugh because Bissell and the ATC have spent the last two years publicly, if civilly, butting heads. Two summers ago, after ultrarunner Scott Jurek completed a record-setting and much-hyped thru-run of the Appalachian Trail — culminating on Katahdin, the AT’s northern terminus — Bissell took to the park’s Facebook page to scold the runner and his crew for sullying “Maine’s largest wilderness” with a corporate-sponsored media event, revealing that a ranger had cited Team Jurek for, among other things, public consumption of celebratory champagne and filming at the summit in violation of its media permit. “The AT is apparently comfortable with the fit of this type of event in its mission,” Bissell wrote, adding that Baxter State Park has no obligation to host the trail and that its governing authority would consider “if a continued relationship is in [its] best interests.”

Bissell’s rebuke prompted outlets from Backpacker to The New York Times to report on the director’s long-simmering concerns about swelling numbers of AT hikers taxing the park’s resources and diminishing its wilderness character. In 1991, the park recorded 359 long-distance AT hikers attempting Katahdin. Last year, it logged 2,733. The Times in particular played up a line from a little-publicized open letter Bissell had written to ATC officials in 2014, suggesting that reducing hiker impacts might involve “relocating key trail portions or the trail terminus.”

“Officials here are threatening to reroute the end of the trail off Katahdin,” wrote Katharine Q. Seelye, the paper’s New England bureau chief. “The very idea has stunned the hiking world.”

There is no other park in America quite like Baxter State Park. In its founding, funding, and management, Baxter represents a trio of conditions that are unusual in themselves and unique in tandem.

Then, this year, Bissell further rankled that world — pockets of it, anyway — by capping the number of permits that allow AT hikers to ascend Katahdin without a much-coveted parking or camping reservation. The limit of 3,150 permits represents an increase over last year’s hiker total, but the ATC nonetheless objected, criticizing the move as “not based on best practices, sufficient research, or analysis of the current impact.”

Such policies and rhetoric have earned Bissell derision among some hikers, particularly in online forums frequented by trail junkies. “Jensen Bissell is a loon,” groused one hiker on whiteblaze.net, an AT message-board hub with nearly 70,000 members. “Thru-hikers have two choices. Obey the rules and deal with the overzealous persecution or find an alternative.” Other posters decried “the Tent Police” and “Bissell and the rest of the storm troopers in Baxter State Park.”

“Jensen Bissell only wants us to enjoy [the park] his way,” griped one commenter on Bissell’s original Jurek-chiding Facebook post. “Sounds like some crazy dictator or crackpot that sits on his imaginary throne atop Katahdin.”

“Those old-head do-gooders at Baxter exercise far too much power,” proclaimed another whiteblaze.net commenter. “What good is a park if the public cannot use it?”

Crucially, he also provided for both the park’s financial future and its independent governance, establishing an endowment with his personal bank (untouchable by politicians or bureaucrats) and a three-member board of trustees called the Baxter State Park Authority, consisting of the director of the Maine Forest Service, the commissioner of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife, and the state attorney general. As such, Baxter is a “state park” in only the loosest sense — the state owns the land, but the park has received no state appropriations since 1972 (following Governor Baxter’s death, when his endowment became available), and it isn’t managed by the Bureau of Parks and Lands or otherwise subject to the whims of state government. Baxter State Park is an anomalous and quasi-independent public trust.

What’s more, it has a set of near-sacred founding texts that underpin its management. In both their legal authority and occasional passages of heart-swell quotability, Governor Baxter’s deeds and correspondence are not unlike the Constitution and Bill of Rights. (The title of historian Trudy Irene Scee’s 1999 park chronicle, In the Deeds We Trust, gives some idea of the allegiance they command.) And in a few provocative ways, the vision that Baxter laid out in those documents is considerably less ambiguous than many other public lands charters.

Consider this line, from a 1955 legislative rider to the deeds, elaborating on Baxter’s intent, now regarded as something of a mission statement:

This area is to be maintained primarily as a Wilderness and recreational purposes are to be regarded as of secondary importance and shall not encroach upon the main objective of this area which is to be “Forever Wild.”

This area is to be maintained primarily as a Wilderness and recreational purposes are to be regarded as of secondary importance and shall not encroach upon the main objective of this area which is to be “Forever Wild.”

It’s a statement that predates the federal Wilderness Act by nearly a decade — and does more than that 4,000-word document to confer upon wilderness a value apart from its recreational merits. Today, in an era of perpetual handwringing over definitions of “multiple use” on agency lands, at a time when Ken Burns can make a 12-hour documentary plumbing the “democratic tension” between preservation and recreation at the heart of the National Park Service, Baxter’s clarity of purpose is rare and refreshing. Wilderness comes first, full stop. Then everything else. Maybe.

Bissell, clad in his typical uniform of khakis and a Baxter State Park polo, was manning the front door, handing out numbered slips for the reservations queue. Many in line greeted him by his first name, and I tried to think of another marquee park where the head honcho personally welcomes guests to the visitor center; this is not how Acadia rolls. The whole scene felt clubby, even a little clique-ish.

“I’ve run into issues where people say, you know, you guys are like a cult to me,” Bissell told the Colby crowd this summer. “And, yep, guilty. You could call it that.”

Some 71,000 people passed through Baxter’s gates last year, a number that Bissell considers on the upper end of comfortable. Visitation peaked in the early to mid-’90s, with around 83,000 visitors per year (“a little crowded”), then slid gradually to below 60,000 in the mid-2000s (“a really comfortable number”), and the trend has basically been upward ever since. The greatest challenge of Bissell’s job is mitigating the impacts of that upsurge on the “wilderness experience” — without alienating more outdoorspeople than absolutely necessary.

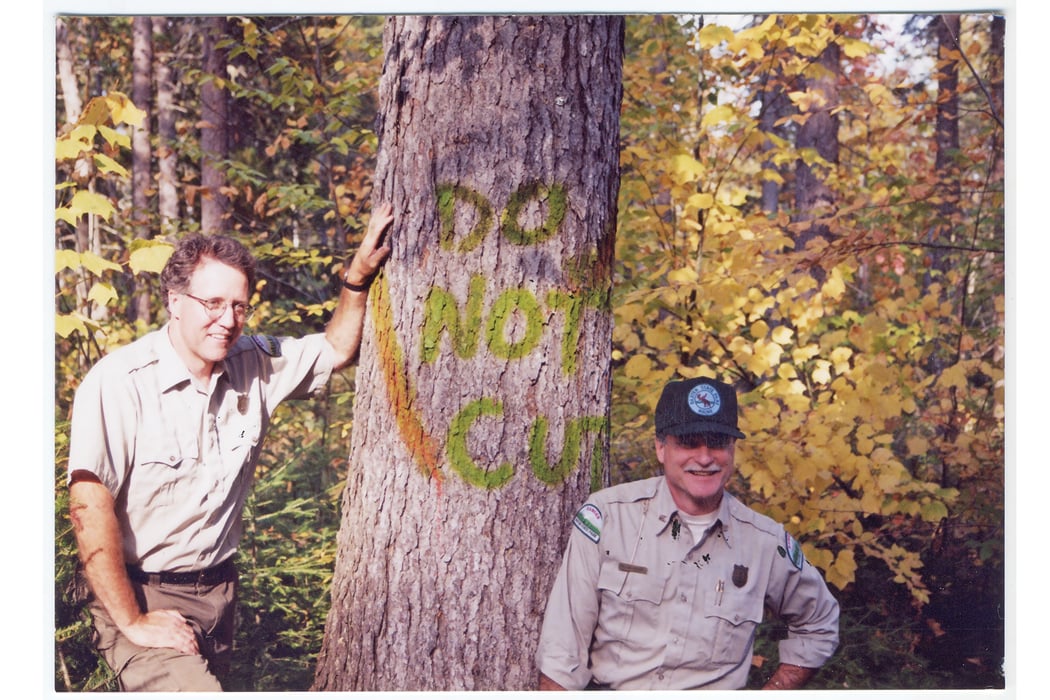

In one sense, Bissell seems an unlikely wilderness defender. Raised in upstate New York, he’s a career forester who cut his teeth working for the Bureau of Land Management in Oregon, nine years of both fieldwork and paper-pushing at a time, he says, when “the Bureau was a woodcutting machine, right or wrong.” He came to Baxter 30 years ago to oversee its Scientific Forest Management Area, 30,000 acres in the park’s northwest corner that Governor Baxter set aside as “a showplace for those interested in forestry . . . wherein the State may practice the most modern methods of forest control, reforestation, and production.” (The other 86 percent of the park is off-limits to logging.) Bissell is widely credited for instituting a profitable, sustainable harvest in what had been a neglected, then hastily cut corner of the park. He became director in 2005 with the endorsement of his retiring predecessor, Irwin “Buzz” Caverly, a North Woods eminence who held the job 24 years and fielded his own share of criticism for heavy-handed rule enforcement.

When I visited Bissell at park headquarters this spring, I copped to occasionally empathizing with the surly online hikers who find some Baxter regulations exasperating. To hike Katahdin, for example, requires a reservation throughout most of the summer and fall — either for a campsite or a day-use parking spot. But a day-use parking reservation (known to staff as a DUPR, pronounced “dooper”) requires one’s presence at the gate by 7 a.m. — a minute later and the space is relinquished to the reservation-less hopefuls who line up outside Baxter at dawn in high season.

I have felt the sting of arriving at 7:10, only to be told Katahdin is off-limits. When I told Bissell this, he smiled sympathetically. “From a human standpoint,” he said, “we don’t like to be told we can’t do something — this idea of limits is just against us naturally. But people get it. They do understand why. If they’ve hiked up there on a crowded Saturday, there are still going to be over 400 people starting up three Katahdin trailheads.”

I have also griped, I admitted, about the park’s ban on hiking above tree line with kids under 6, and I’ve bristled at rangers who’ve stopped me at trailheads to question my footwear or my start time (I am not an early riser), sometimes getting the feeling they’re trying to spook me off the trail.

“Yeah,” Bissell said, “that part’s probably true.” He leaned forward in his chair. “The thing that spooks us the most is the people who don’t have a clue — so we try to spook everybody a little. If you have that experience, you know what we’re doing, and if you don’t, it’ll at least plant the seed that, hey, you should be a little careful about this.”

Compared to, say, mountainous national parks out West, Baxter has a substantially higher percentage of visitors who end up needing help. One of roughly every 2,000 Baxter users is involved in an incident of medical need or a search-and-rescue event. Even in a bad year, that number at the Grand Canyon is closer to one in 10,000. Because Katahdin is both renowned and fairly accessible, Bissell says many assume it’s a less-than-strenuous hike, or that staff is on hand to assist them. A lot of psy-ops goes into dispelling them of these notions. Rangers are trained to “triage” hikers in the parking lot, singling out those who might benefit from words of caution. Blunt signage — “You’re entering Maine’s largest wilderness . . . Rescuers can be many hours in arriving” — appears a half-mile up each Katahdin trail, to be read when Bissell suspects hikers are more receptive to their messaging than at the adrenaline-filled moment of departure.

Bissell is thoughtful and deliberate about such management decisions; in conversation, anyway, he doesn’t come off like a megalomaniacal wilderness despot. He himself has lobbied the Authority for some less restrictive policies (pushing for expanded winter use, for example). Of late, he’s championed permitting dogs — which are prohibited park-wide — in the portion of the park open to logging, but he’s had little success winning over his staff and volunteer advisory board. “I’ve come to the conclusion that I’m a single, solitary light here,” he told me, reaching down to pat Effie, the poodle mix that often accompanies him to his Millinocket office. “I haven’t been able to sell anybody else on it, so I shouldn’t do it. Because jamming something down somebody’s throat is not the way to conduct good policy.”

But where Bissell’s critics can see an overbearing traditionalist, his colleagues see a proactive champion for Governor Baxter’s wilderness mandate. “Our job isn’t to say what we would like to have happen personally,” reminds Attorney General and Baxter State Park Authority member Janet Mills, “but what Percival Baxter would want to have happen, channeling his views.” (Indeed, when Bissell spoke at Colby — where the crowd was quite respectful — I briefly imagined a drinking game in which participants chugged whenever he mentioned “the donor,” his reverent term for the park’s founding father.)

“The park director’s job is not easy,” says Steve Rowe, who preceded Mills as AG and served as Authority chair for much of his eight-year tenure. “Many people don’t appreciate the unique nature of Baxter, and others simply disagree with park policies because they find them too restrictive. Jensen has steadfastly stood up to those who’d put human recreation over protection of the park’s natural resources.”

Bissell, for his part, does not read the comments. He knew what he was getting into, he says, with his statements on Jurek and the thru-hiker hordes. “I recognized I was putting something out publicly that would concern this huge culture of AT people,” he says. “You’re getting into something that’s really important to people — they’re going to respond.” Since then, he says that Baxter and the ATC have “made really great progress.” A new AT visitor center in Monson helps educate hikers on Baxter’s rules and culture and ways to mitigate their impact. A multi-stakeholder task force has monthly calls to discuss concerns. But as of early September, the park had already issued 2,000 out of 3,150 AT hiker permits, with the real crush of northbound AT thru-hikers just beginning. Should the AT keep attracting more and more thru-hikers — a scenario that doesn’t seem to alarm the ATC — Bissell still sees trouble down the line. “I just cannot mesh these models,” he says. “They want to continually increase this use number, and we can’t. And we won’t.”

Recently, I joined Bissell on a hike up Baxter’s Mount OJI, a steep 3 miles through cedar swamp and hardwood stands, reaching a 3,410-foot summit surrounded by exposed ledges with terrific views. Bissell helped plot a reroute of the trail a few years back, and he paused here and there to admire the flow of it over dirt and granite. Forecasts had called for rain, but it was a great day for a hike, cool and overcast, and Bissell was feeling reflective.

He’s had a hard year. Last November, he lost his wife, Sheilah, quite unexpectedly, at age 62. He’s spent some extra time since then with his sons, who run Portland’s Bissell Brothers Brewing Company, and who are working to open a second location in their hometown of Milo, where Bissell still lives. As we hiked, Bissell reminisced about taking his kids on their first few summit trips, about the way they’d look scared but want to press on even after he’d offered to turn back. At one point, he got teary while telling me about a 24-year-old man killed by lightning in the park some years ago, and I could tell he was thinking about his own boys.

At an overlook near the summit, the clouds lifted to reveal a deep green basin below, the woolly and trail-less plateau known as the Klondike, which has been called the park’s “purest wilderness.”

“I never get tired of looking at that,” Bissell breathed. He says he doesn’t get to hike as much as he’d like to these days. Later, he told me, wistfully, “I look forward, and I have for years, to be able to come in here and camp just as you would.”

As we came down the mountain that afternoon, I asked Bissell whether he wanted new visitors to come to Baxter State Park, or whether he sometimes found himself wishing they’d just go someplace else. “That might happen,” he admitted. “But I think there’s still a fair amount of room in the park to accommodate people on trails they’ll enjoy — it’s just not going to be on Katahdin. So I really don’t know where that limit is.”

A few minutes later, we passed another hiker, the only one we saw all day, a trim European with a floppy hat and trekking poles. He paused, smiled at us, and, in an accent that might have been Dutch, asked whether we knew this mountain well. Bissell said that he did.