By Kristen Lindquist

From the February 2016 issue

Long before Harry Potter’s snowy owl Hedwig became a pop culture star, I was fascinated by the charismatic white bird. As a kid, I covered my bedroom wall with owl posters torn from Ranger Rick magazines. I secretly wished someone in my family smoked White Owl cigars so I could keep the box. The thought of someday actually seeing a snowy owl in the wild seemed about as likely to me as glimpsing that other magical white creature I was obsessed with, the unicorn.

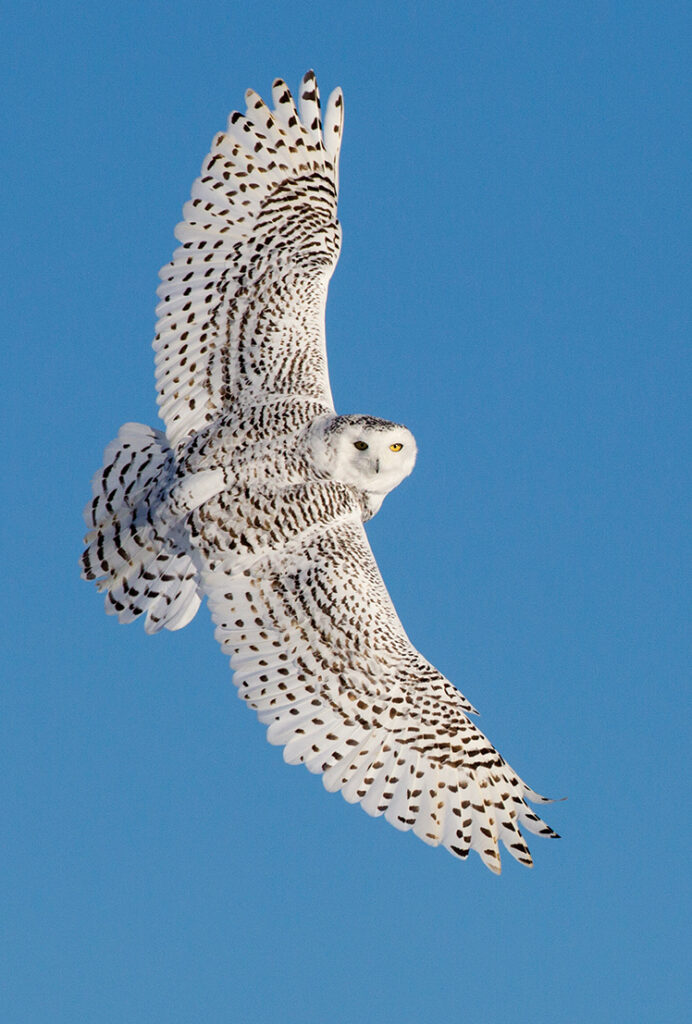

So of course I remember well seeing my first one, years later, on the burnt-over blueberry barrens atop Union’s windswept Clarry Hill, the bird’s fierce yellow eyes visible even at a distance. I stood there shivering for a long time, savoring the moment, trying to imagine what those eyes had witnessed on the vast tundra: polar bears? Northern lights? Eventually, the owl spread its ghostly white wings and floated soundlessly out of sight, and I let out a long, joyful sigh.

While common on its home turf in the Canadian high Arctic, the snowy owl can be elusive here in Maine. Its winter incursions are so sporadic that any one visit can feel especially portentous. In a season when most birds, and many humans, flee Maine for warmer climes, the owl arrives: a serene and enigmatic emissary from a polar realm even colder and harsher than our own, so distant and strange that it might as well be Hogwarts.

And for the past two winters, arrive they did, in an explosion of birds known in birding parlance as an “irruption.” Beginning in fall 2013, thousands of snowy owls — rather than the usual few dozen — showed up farther south than usual, especially in the eastern United States, with single birds reported as far south as Florida and Bermuda. Boston, New York, Baltimore, and Washington, DC, all hosted owls. Here in New England, the arrival of so many snowy owls made for thrilling winter birding: a dozen seen along the tiny strip of coastal New Hampshire; three or four in one scope view at Popham Beach; 10 found in one day at Biddeford Pool by a photographer friend on an owl quest; six or seven hanging out in Aroostook County potato fields. Everyone, it seems, had a snowy owl story to share. Last winter was almost as exciting. Birders and nature photographers weren’t the only ones hoping it would happen again this winter.

In the past, snowy owl irruptions have been tied to lemming population crashes. The sudden shortage of their key prey forces starving birds to travel thousands of miles from their Arctic habitat to find other food sources. However, the majority of owls that wandered southward these past two winters were apparently healthy and well fed. Field researchers in the Arctic noted that nesting owls there had caught more lemmings than they’d known what to do with. One nest in Canada’s remote northern Nunavut territory was photographed with more than 70 lemmings stacked around it. This overabundance of food enabled more chicks than usual to survive. But mature adults dominate the hunting grounds, so once fledged, the youngsters dispersed. For dozens of them, the New England coast became their stocked refrigerator that first winter. And many came back for more last winter.

Irruptions are cyclical, occurring every few years and linked to the abundance prey. Based on nesting observations this past summer, ornithologists predicted that snowies would show up in the Midwest and Pacific Coast this winter. And indeed, by the end of October, more than 50 snowy owl sightings in the Great Lakes region were posted to eBird, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s online database of bird observations, weeks before any had been posted in Maine.

But even if Maine doesn’t experience another owl snowstorm this winter, it’s always worth looking. Many of those that hatched in the summer of 2013 are still out there — snowy owls can live to more than 10 years old — so winter hunting ranges may continue to be cramped in the Arctic. And Maine, especially the coast, offers an attractive landscape for a nomadic bird whose favorite foods include rodents and sea ducks.

To see a snowy owl, try to think like one. This efficient hunter uses its super-sharp eyesight and hearing (and huge talons) to hunt both day and night over open tundra, or what passes for it here in Maine — beaches, farm fields, blueberry barrens, and frozen marshes. Airports are another good place to spot them, but a bird with a 4-foot-plus wingspan is not especially welcome near the runways for safety reasons.

Sometimes, neither are birdwatchers. The only person I’ve ever met who was not immediately charmed by a snowy owl was an elderly sheriff’s deputy at my local airport. My husband and I had pulled off the road to watch an owl perched on a fence bordering the runway. To the deputy, we (and the owl) were just one big security risk, and he quickly made us move along. He had obviously never read Harry Potter.